In the music industry, the artists who put the most time and effort into creating unique visuals tend to be one-named pop stars: Beyoncé, Madonna, Björk. Caroline Polachek may be a first-name, last-name kind of artist, but over the last three-plus years, it’s become evident she has a talent for building immersive aesthetic worlds around her music. Across her album art, styling, music videos, and tour sets, Polachek’s approach is meticulous, thoughtful, and decidedly her own.

Polachek broke out in the 2000s with the indie band Chairlift, but the modern era of her music and visual storytelling arguably begins with 2019’s Pang, the first album released under her own name. An angsty, deeply internal record that became an uncanny fit for the early months of COVID-19 lockdown, Pang came with imagery that evoked a cold, salt-soaked North, full of mist, corsets, stormy skies, and Celtic-leaning typefaces. This past Valentine’s Day, Polachek released her new album, Desire, I Want to Turn Into You. Its look was hotter, sweatier, and pleasingly messy—a representation of the post-quarantine urge to fling oneself back into the world.

You could write a term paper about Polachek’s visuals, they’re so rich with allusions and recurring motifs. Indeed, during a cameras-off Zoom interview with the musician, I had the distinct feeling of being in class with the coolest young professor on campus. Polachek spoke lucidly and in detail, her voice emanating from the black rectangle of my screen in nearly complete paragraphs.

The visuals for Pang were the product of what Polachek describes as an “aesthetic conundrum.” Having traversed the Brooklyn indie scene with Chairlift, she was spending time around electronic artists affiliated with London’s PC Music label, which had its own visual fingerprint. “[It] was really playing with a lot of contemporary commercial aesthetics, playing in a very tricksy way with the idea of advertising language, advertising visuals, hyper-airbrushed photography—but using it in a very self-aware way that I think preceded a lot of what became pop aesthetics now,” Polachek says.

The songs she was writing had aspects of folk, psychedelic, and classical music, but she was making them with tools that, in the hands of her peers, were infused with that commercial visual language. “I kept asking myself, how can I reconcile these two worlds?” Polachek says. “How do I connect this sort of folkloric attitude with something that feels like it exists online?”

Pang combines a sleek digital look with strong elements of high fantasy, thanks to the presence of glowing orbs, large keys, and a spiky, snaking, otherworldly gate designed by Timothy Luke that appears in the album art and eventually served as Polachek’s tour set. “The gate became this really important symbolic motif throughout the album, of this conflict between possibility and frustration,” Polachek says. (A gate is, after all, both an entrance and an impediment.) For her set design, she looked to the work of Eyvind Earle, the Disney background artist who, in the 1950s, gave the forests and castles of Sleeping Beauty their striking vertical lines.

“[Earle] was chewing on the same sort of aesthetic problematic as I was. He was dealing with medieval imagery in Sleeping Beauty, these stories set in ancient times, but at the same time trying to give these Disney films a sense of cutting-edge modernity,” she says. “Of course, rather than bringing in the language of brutalist architecture, I was bringing in the language of the internet.”

For those who doubt—persistently, exhaustingly—that a female musician can be the mastermind behind her own work as well as the face of it, let it be known that Polachek is running her own operation. At 38, she isn’t signed to a record label, and although she works with a constellation of collaborators across her music and visuals, several of those people describe her, in positive terms, as unusually hands-on for an artist at her level.

In addition to writing and producing her own music, Polachek typically directs and edits her music videos with her boyfriend, the artist Matt Copson. She’s the one discussing photo edits and hashing out the details of a project over WhatsApp. “It’s all in her head,” says photographer Aidan Zamiri, a self-professed fan who began working with Polachek after she reached out via DM.

Polachek collects reference imagery in a “painfully detailed” file system that not only prevents her from losing track of things (“the worst feeling ever”), but also helps her see the threads running through her work. Both Zamiri and Hatty Ellis-Coward, one half of the set design team behind Studio Augmenta, which has created sets for Polachek’s photo shoots, told me they see a lot of mood boards that look the same. There’s a lot of tired Y2K imagery going around, for instance. Polachek, on the other hand, surfaces “esoteric references that are unusual and well researched,” says Ellis-Coward, who observed that the artist’s style seems to exist outside of current trends.

Carly Mark, designer of New York fashion brand Puppets and Puppets, believes Polachek is able to execute on her vision because of this organized approach to creativity. Polachek has walked in several of Mark’s runway shows—she opened spring/summer 2023 in a dress that completely exposed her chest, which was adorned with three-dimensional butterflies—and the designer counts her as a rich source of feedback and reference material. “I’ve gotten texts from her being like, ‘I found this archival costume top. It’s really well made. I’ve never seen anything like it. Here’s a picture of it from every angle, take what you want from it,’” Mark says.

In contrast to the aching interiority of Pang, Polachek has described the energy of Desire, I Want to Turn Into You as hot-blooded, bratty, manic, funny, a bid for catharsis as the world reopened. “I started feeling very intensely that the role of the artist is to remind us that this kind of chaos has been around forever, that this kind of chaos is normal, in fact,” she tells me. “I wanted to celebrate that, on a very subliminal level running through this album, feeling awash in uncertainty is not only okay, but is kind of eternal and playful and can be humorous and sexy and vital.”

Desire is full of references to antiquity that evoke that timeless chaos: Pursued by a minotaur, Polachek slinks through a labyrinth made of cardboard boxes in the music video for “Bunny Is a Rider” and serves as the singing head of a sphinx-like sculpture in “Welcome to My Island.”

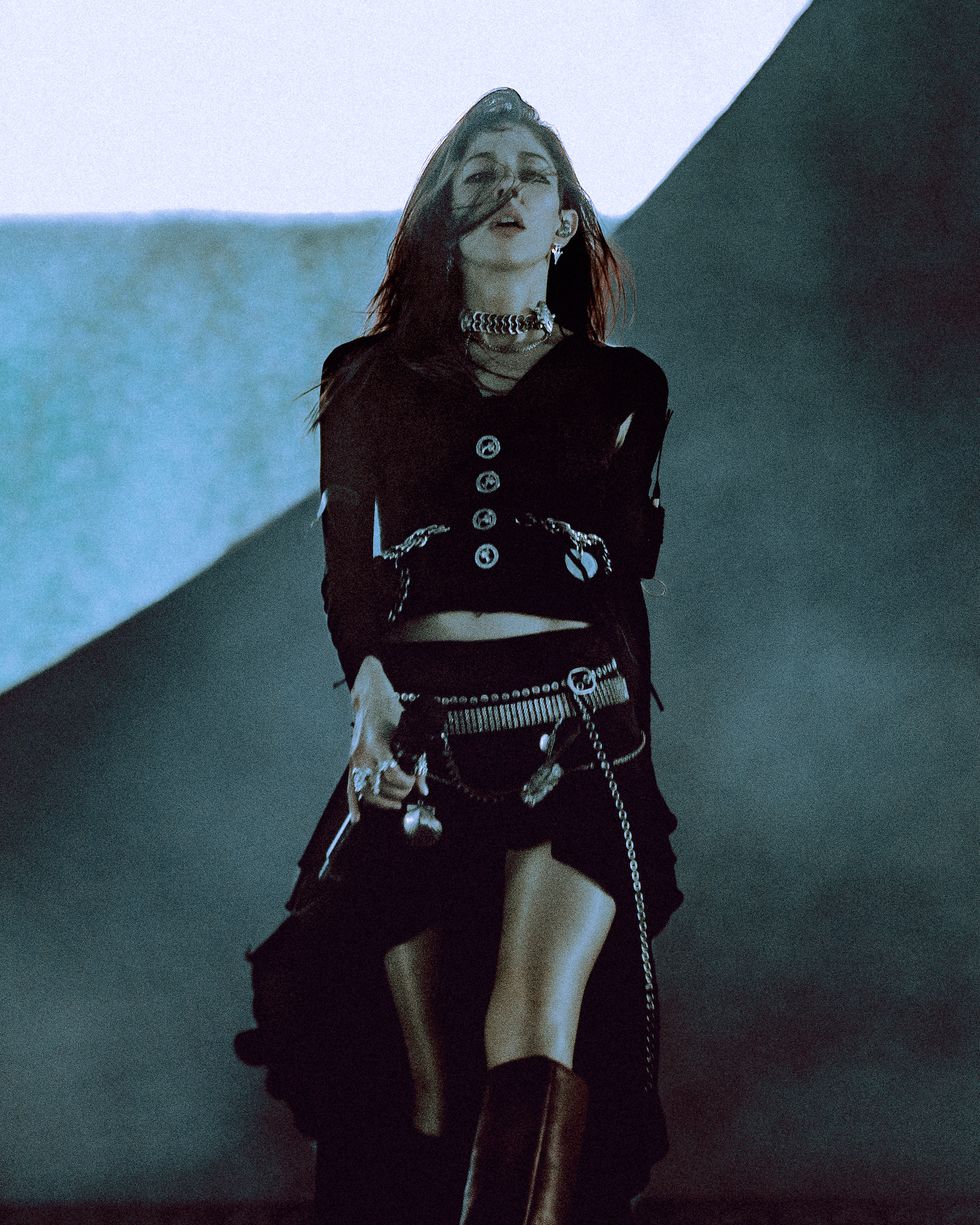

In her album art and recent tour looks, she has gravitated toward pieces that are imbued with a sense of history and mythology, including jewelry by the Brooklyn brand Plutonia Blue and clothing from the London-based labels Genevieve Devine and Kepler. Polachek pairs some of her more arcane pieces—like a chain belt adorned with rocks and a functional cigarette lighter, created by the artist Corrina Goutos—with modern, casual clothing items like baby tees, board shorts, and American Apparel–esque bodysuits.

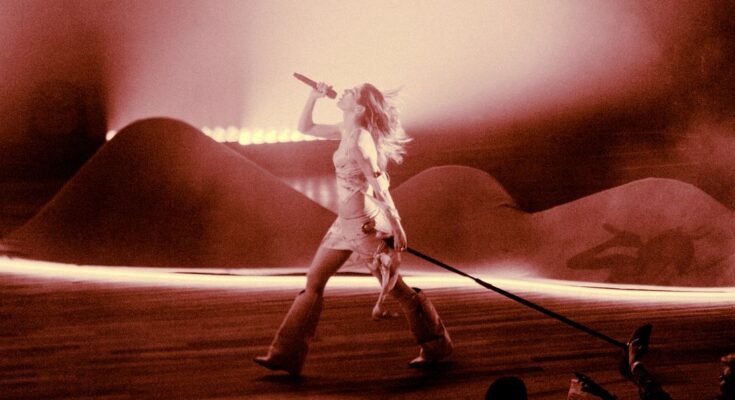

Above all, Polachek’s Desire styling shows evidence of living in the world. “It’s not glossy, it’s not put-together, it’s not fashion with a capital F,” she says. On the cover of the album, she crawls through a London Tube car wearing a coffee-stained dress. Faux sunburns revealing swirls of pale skin have become a hallmark of her promo photos and performances, including her March set on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon. “I want everything to feel caught in between, caught in transit, on its way somewhere, traces of where it’s just been,” she says.

Given the depth of Polachek’s world-building practice, it may not come as a surprise that she likes wearing what is essentially the same outfit to the studio every day when recording. “It kind of grounds me in a sense of character, and often what that outfit is ends up being kind of aspirational, like something that I want the music to sound like or feel like,” she says.

While recording Desire, she took to wearing inexpensive cooking aprons. Turns out it’s easy to make a DIY backless dress out of a few aprons: Put one over your head and tie it in the back, then wrap a second around your butt and tie it in the front. Polachek likes the humor of this look, the inherent sexiness of an open back, the refreshingly anti-fashion nature of an outfit made from standard-issue aprons, the fact that you can spill anything on it. “I kind of find it the perfect modular clothing,” she says.

Celebrity styling, and by extension celebrity image-making, leans so heavily toward newness that it makes headlines when Cate Blanchett re-wears a red-carpet look. But Polachek’s world is immersive and potent precisely because of her tendency to repeat melodies, outfits, and motifs, from her gates and minotaurs and spirals to her aprons and regular array of silver rings (a mix of flea-market and pawnshop finds, as well as a Mondo Mondo ring with glass insets and an enormous, roughly hewn spiral by Plutonia Blue). Repetition transforms an outfit from a cool thing a musician wore in a certain context to an essential and meaningful expression of their perspective.

“I think something really clicked for me when I was looking at pictures of Kurt Cobain and seeing him wear the same sunglasses in every photo,” Polachek says. There’s a feeling of familiarity that comes with witnessing another person’s relationship to their stuff, and that, in an odd twist, has an aspirational quality. “Seeing him with the same sunglasses really taught me, Oh, that’s what style is,” Polachek says. “Style instantly became more important to me than fashion, which is just to say that style is the thing you repeat. It’s the shape you like to wear a lot. It’s the things you don’t ever wear. It’s that thing that makes you you.”